We were around twelve years old when the video came in the mail: NFL's "Crunch Course," the freebie a subscription to Sports Illustrated got you in the football phone giveaway days. ("Yeah, honey--it's a football...and a phone! I'M NOT KIDDING!") In pre-internet, pre-126 channel cable days, an effective strategy for whiling the afternoon away when you didn't want to be climbing trees, learning something, or otherwise expending precious effort was watching videotapes repeatedly until the tape broke. The only provision was that the movie in question be so irredeemably entertaining that 382 consecutive viewings would only enhance the beauty of the images strobing out of the electron gun and onto the screen. This sounds like a problem until you remember that 12 year olds have very, very low standards of entertainment, and will do anything to avoid productive behavior.

It's a football...and a phone!

Crunch Course had addiction written all over it--it elicited oohs and aahs we didn't even know were coming from our mouth. (When we had insomnia we'd watch it, which combined with the noises probably convinced Mom that we'd started masturbating, and that knocking would be a prerequisite from that point on. )

The video represented NFL films attempt to capture all of the mid-80s badasses of football in one slow motion paean to XYY males: Howie Long, Lawrence Taylor, and most movingly, Walter Payton. His segment of the film portrayed him as the dimunitive, devastating right hand of an angry Jehovah bent on jacking linebackers in the jaw until the world was free of sin. It also burned a blueprint of his absolute invincibility on our hard drive; when we watched his press conference years later, the one where Payton announced he was dying, a reporter asked him if he was scared. He started crying in response, and we couldn't help but weep on sight, too. Reconciling the image of the emaciated man wearing sunglasses and crying his eyes dry on national television with the shots of Payton clad in a tank top and his trademark 'Roos doing wind sprints up a hill shredded by years of workouts--we couldn't ever really make the two cohere. In fact, we're still not totally convinced he's not going to come in the door, stiff arm us in the face, and hitch-step his way out the door.

Still not dead.

The film, though, brought one thing home powerfully to our young brain. Sport, more than theater, more than film, more than any other form of what you might call visual entertainment, was truly random and unpredictable.

And in sport, nothing sold itself so passionately to the eye and the atavistic bloodlust in your head like football. There was a sort of script, sure: plays, strategies, tendencies. When the whole thing moved, though, those could go out the window according to the whims of the gods, mother nature, and the hiccups of the human nervous system.

Crunch Course captured it in crystalline snippets of distilled, choice violence. Frank Gifford getting clotheslined by Chuck Bednarik, his body becoming a spindly tail whipped to the ground by the force of impact. A young Dick Butkus talking about how he dreamed of hitting someone so hard their head flew from their body. Lawrence Taylor tossing aside linemen and tight ends like they were bowling pins. Payton burying the heel of his palm into a linebacker's chin, the forearm disappearing deep into the facemask. The Nat Moore "helicopter" hit. Football suddenly became more than just fireworks for the eye; it became visceral, fascinating to the point of fixation, and compelling like watching sheets of ice crash from the side of a melting glacier.

What makes it beautiful, then? This article attempts to parse out precisely what makes sport in general beautiful, but what we're concerned with is what makes football (particularly college) so damn arresting. Point by point.

The violence. Yeah, the violence. Mike Leach admits it. So does Urban Meyer. Watching football unfold live before you is like watching the Discovery Channel's sweeps week lineup of animal violence play out before your eyes. The lines tussle like elephant seals gouging each other over mating territory. Wide receivers and dbs chase each other down like gazelles and cheetahs burning across the savanna. Linebackers and running backs=rams...you get the overly reinforced metaphor. Something in that lizard brain loves, needs, and craves physical conflict; something that can trigger the fight or flight survival mechanism without actually engaging the potentially risky actual fight or exhausting flight. A form of drug humans are wired to respond to can't be denied, and football is just that, a visual stimulus not unlike a drug for the senses altering body chemistry dependent on wins and losses. Cliched as it sounds, sports can be proxy survival drama for the civilized set: evolutionary struggle without the messy casualties. Whether this is methadone for a necessarily subdued addiction to the heroin of actual cutthroat competition or an analog for real life--that's a sociobiological question we decline to touch with a ten-foot pole.

Earl Campbell: breathtaking, heartstopping violence in powder blue.

The Random and Unpredictable. No one likes a fixed contest. Even professional wrestling acknowledges this fact through improvising much of the action on the way to a predetermined finish, thus livening up what could be a dreary, obvious progression to a prearranged finale involving folding chair, tacks, fire, and hopefully a topless girlfriend/moll/wife. Football games begin with a plan and devolve into ordered sequences of play shaped by a grab-bag of squirelly indeterminables: the weather, mood, physical conditioning, injury, acts of god, lighting, logistical problems, brain farts by players, the matchup of one randomly selected play against another, accidents of physics, marginally probable realities...all align to create the full, fluid system dictating the events happening on the field. An official notices a jet plane's lights trailing against the Knoxville sky...and just happens to miss Jonathan Wade slapping Dallas Baker, who then retaliates and earns an unsportsmanlike conduct penalty that gives Tennessee field goal position and hence the game. The random is cruel. It is unfair. But as any gambling addict will tell you, despite the obvious trends that make beating the system unlikely, it's the hope and anticipation of doing so that keep the monkeys pumping nickels into the slots. The cruelty of loss becomes just a necessary payment for the eventual rush of victory.

The beauty of design. Despite all the randomness, the design can and does prevail in football, mostly through analysis of trends and countering them with practice and playcalling. This is what the esteemed Dr. Hickey refers to as "what to watch for," which would be the savory clicking feeling you get in your brain when watching a safety's head whip around too late on a beautiful play action fly pattern after biting on the run, or witnessing a stunned defense flailing after the upback on a galling fake punt call. It's more of a secondary pleasure, since it's dependent on a whole lot of study and experience with the game and the systems in it. But as anyone who's watched the x's and o's of a game so intently that the world goes silent in your ears, it's among the most intense varities of beauty in the game.

The Physically Improbable. Human note the physically exemplary and unusual. If we didn't, John Holmes wouldn't bring to mind images of radio towers, summer sausage, and other very long, very big cylinders. (The mustache was pretty exemplary, too.)

Football's kinetic violence and design are enough to spellbind, but the mutants playing it add to the jaw-dropping magnetism of the intentional chaos. If you need reminding of what a full-blooded freak looks like, we present the 2006 example: Calvin Johnson of Georgia Tech.

Memory. Kyle wrote best about this--memory and blood can tie someone to college football with the strength of a covalent bond, particularly if you're a football fan of the inherited variety. (Which we're not, which is likely why the Proustian section of the piece begins all the way down here. The college football memoir would be triggered by the bite of a tasty Bryan's hot dog in place of the madeleine.) Going to games brings with it the attendant weight and import of memories shared with fathers, grandfathers, brothers, moms, sisters, cousins, friends...it brings a weight that (as Rammer Jammer details exhaustively) turns simple athletic events into a series of rites on par with religion. We freely admit that as a nigh-30 year old, we're only starting to get the inky dark heart of this side of the game--which may be the most beautiful thing of all.

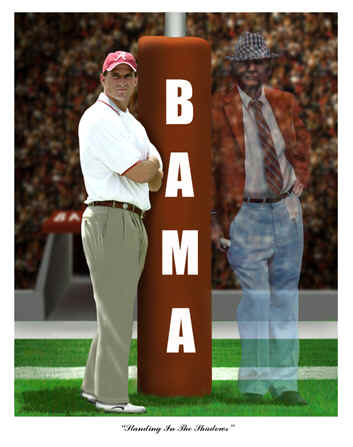

Exhibit A.